Vanishing Point is a 1971 American action film directed by Richard C. Sarafian, starring Barry Newman, Cleavon Little, and Dean Jagger. It focuses on a disaffected ex-policeman and race driver delivering a muscle car cross country to California while high on speed ('uppers'), being chased by police, and meeting various characters along the way. Since its release it has developed a cult following.

Vanishing Point is a 1971 American action film directed by Richard C. Sarafian, starring Barry Newman, Cleavon Little, and Dean Jagger. It focuses on a disaffected ex-policeman and race driver delivering a muscle car cross country to California while high on speed ('uppers'), being chased by police, and meeting various characters along the way. Since its release it has developed a cult following.

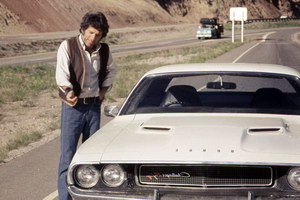

Kowalski, works for a car delivery service. He takes delivery of a 1970 Dodge Challenger to take from Colorado to San Fransisco, California. Shortly after pickup, he takes a bet to get the car there in less than 15 hours. After a few run-ins with motorcycle cops and highway patrol they start a chase to bring him into custody.

Along the way, Kowalski is guided by Supersoul - a blind DJ with a police radio scanner. Throw in lots of chase scenes, gay hitchhikers, a naked woman riding a motorbike, lots of Mopar and you've got a great cult hit from the early 70's.With a plaintive, desert-baked guitar acting as soundtrack, Richard C. Sarafian's existential action epic Vanishing Point begins at its end, with rust-speckled bulldozers rumbling through the morning light of a funereal California town apparently populated only by doddering old men with ancient hats. As helicopters dot the air, these earth-movers situate themselves imposingly in Main Street's middle as a makeshift roadblock. They're the law's last stab at halting a determined, enigmatic force named Kowalski (Barry Newman), who's about to spend the rest of this melancholy, pepped-up movie muscling towards San Francisco in high-speed flashback.

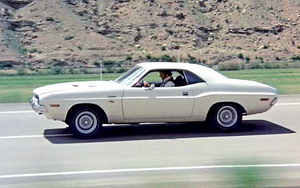

Car delivery driver Kowalski arrives in Denver, Colorado, on a late Friday night with a black Imperial. The delivery service clerk, Sandy, urges him to get some rest, but Kowalski insists on getting started with his next assignment: deliver a white 1970 Dodge Challenger R/T 440 Magnum (fitted with a supercharger, for top speeds of over 160 miles per hour) to San Francisco by Monday. Before leaving Denver, Kowalski pulls into a biker bar parking lot around midnight to buy Benzedrine pills to stay awake for the long drive ahead. He bets his dealer Jake that he will get to San Francisco by 3:00 pm Sunday, even though the delivery is not due until Monday.

Car delivery driver Kowalski arrives in Denver, Colorado, on a late Friday night with a black Imperial. The delivery service clerk, Sandy, urges him to get some rest, but Kowalski insists on getting started with his next assignment: deliver a white 1970 Dodge Challenger R/T 440 Magnum (fitted with a supercharger, for top speeds of over 160 miles per hour) to San Francisco by Monday. Before leaving Denver, Kowalski pulls into a biker bar parking lot around midnight to buy Benzedrine pills to stay awake for the long drive ahead. He bets his dealer Jake that he will get to San Francisco by 3:00 pm Sunday, even though the delivery is not due until Monday.

Through flashbacks and the police reading of his record, we learn that Kowalski is a Medal of Honor Vietnam War veteran, former race car driver, and motorcycle racer. He is also a former police officer, who was expelled from the force after he prevents the rape of a young woman by his superior.

Driving west across Colorado, Kowalski is pursued by two motorcycle police officers who try to stop him for speeding. He forces one officer off the road and eludes the other officer by jumping across a dry creek bed. Later, the driver of a Jaguar E-Type roadster pulls up alongside Kowalski and challenges him to a race. After the Jaguar driver nearly runs him off the road, Kowalski overtakes him and beats the Jaguar to a one-lane bridge, causing the Jaguar to crash into the river. Kowalski checks to see if the driver is okay, then takes off, with police cars in pursuit. Kowalski drives across Utah and into Nevada, with the police unable to catch him. During the pursuit, Kowalski listens to radio station KOW, which is broadcasting from Goldfield, Nevada. A blind black disc jockey, who goes by the name of "Super Soul," listens to the police radio frequency and encourages Kowalski to evade the police. With the help of Super Soul, who calls Kowalski "the last American hero", Kowalski gains the interest of the news media, and people begin to gather at the KOW radio station to offer their support.

During the police chase across Nevada, Kowalski finds himself surrounded and heads offroad into the desert. After he blows a left front tire on a dry lake bed and becomes lost, Kowalski is helped by an old prospector who catches rattlesnakes for a Pentecostal Christian commune. After Kowalski is given fuel, the old man directs him back to the highway. There, he picks up two homosexual hitchhikers stranded en route to San Francisco with a "Just Married" sign in their rear window. When they attempt to hold him up at gunpoint, Kowalski beats them up, and throws them out of the car and continues on his journey.

Super Soul Saturday afternoon, a vengeful off-duty highway patrolman and a group of thugs break into the KOW studio and assault Super Soul and his engineer. Near the California state line, Kowalski is helped by hippie biker, Angel, who gives him pills to help him stay awake. Angel's girlfriend recognizes Kowalski and shows him a collage she made of newspaper articles about how he had prevented the rape of the young woman by the senior police officer. Listening again to the KOW radio broadcast, Kowalski notices a change in tone from Super Soul (after he was beaten by the group of thugs), and now suspects that Super Soul's broadcast is being directed by the police to entrap him in California. Confirming that the police are indeed waiting at the border, Angel helps Kowalski get through the roadblock with the help of an old air raid siren and a small motorbike with a red headlight strapped to the top of the Challenger, simulating a police car. Kowalski finally reaches California by Saturday at 7:12 pm. He calls Jake from a payphone to reassure him that he still intends to deliver the car on Monday, while acknowledging he won't win their bet, and offering to double it for the next time.

Super Soul Saturday afternoon, a vengeful off-duty highway patrolman and a group of thugs break into the KOW studio and assault Super Soul and his engineer. Near the California state line, Kowalski is helped by hippie biker, Angel, who gives him pills to help him stay awake. Angel's girlfriend recognizes Kowalski and shows him a collage she made of newspaper articles about how he had prevented the rape of the young woman by the senior police officer. Listening again to the KOW radio broadcast, Kowalski notices a change in tone from Super Soul (after he was beaten by the group of thugs), and now suspects that Super Soul's broadcast is being directed by the police to entrap him in California. Confirming that the police are indeed waiting at the border, Angel helps Kowalski get through the roadblock with the help of an old air raid siren and a small motorbike with a red headlight strapped to the top of the Challenger, simulating a police car. Kowalski finally reaches California by Saturday at 7:12 pm. He calls Jake from a payphone to reassure him that he still intends to deliver the car on Monday, while acknowledging he won't win their bet, and offering to double it for the next time.

On Sunday morning, California police, who have been tracking Kowalski's movements, set up a roadblock with two bulldozers in the small town of Cisco, which Kowalski will be passing through. A small crowd gathers, some with cameras. Kowalski approaches at high speed; failing to slow down, he smiles as he crashes into the bulldozers, destroying the car in an explosion. As firemen work to put out the flames, the crowd slowly disperses.

Dodge Challenger According to Sarafian, it was Zanuck who came up with the idea of using the new 1970 Dodge Challenger R/T. He wanted to do Chrysler a favor for their longtime practice of renting cars to 20th Century Fox for $1 a day. Many of the other cars featured in the film are also Chrysler products. Stunt Coordinator Carey Loftin said he requested the Dodge Challenger because of the "quality of the torsion bar suspension and for its horsepower" and felt that it was "a real sturdy, good running car."

Dodge Challenger According to Sarafian, it was Zanuck who came up with the idea of using the new 1970 Dodge Challenger R/T. He wanted to do Chrysler a favor for their longtime practice of renting cars to 20th Century Fox for $1 a day. Many of the other cars featured in the film are also Chrysler products. Stunt Coordinator Carey Loftin said he requested the Dodge Challenger because of the "quality of the torsion bar suspension and for its horsepower" and felt that it was "a real sturdy, good running car."

Five Alpine White Dodge Challenger R/Ts were lent to the production by Chrysler for promotional consideration and were returned upon completion of filming. Four cars had 440 engines equipped with four-speed manual transmissions; the fifth car was a 383 with a three-speed automatic. No special equipment was added or modifications made to the cars, except for heavier-duty shock absorbers for the car that jumped over No Name Creek. The Challengers were prepared and maintained for the movie by Max Balchowsky, who also prepared the Mustangs and Chargers for Bullitt (1968). The cars performed to Loftin's satisfaction, although dust came to be a problem. None of the engines were supercharged, but sound effects of a supercharger were added in post-production for some scenes. Loftin remembers that parts were taken out of one car to repair another because they "really ruined a couple of those cars" while jumping ramps between highways and over creeks. Newman remembers that the 440 engines in the cars were so powerful that "it was almost as if there was too much power for the body. You'd put it in first and it would almost rear back!" The Challengers appear in the film with Colorado plates OA-5599.

The film's cinematographer John Alonzo used light-weight Arriflex II cameras, that offered more free movement. Close-up and medium shots were achieved by mounting cameras directly on the vehicles instead of the common practice of filming the drivers from a tow that drove ahead of the targeted vehicle. To convey the appearance of speed, the filmmakers slowed the film rate of the cameras. For example, in the scenes with the Challenger and the Jaguar, the camera's film rate was slowed to half speed. The cars were traveling at approximately 50 miles per hour (80 km/h) so that when projected at normal frame rate, they appeared to be moving much faster.

Vanishing Point was filmed on location in the American Southwest in the states of Colorado, Utah, Nevada, and California:

- Austin, Nevada

- Cisco, Utah (the ending)

- Denver, Colorado

- Esmeralda County, Nevada

- Glenwood Springs, Colorado (first motorcycle police chase)

- Goldfield, Nevada (Super Soul scenes)

- Interstate 70 in Utah

- Lander County, Nevada

- Nye County, Nevada

- Rifle, Colorado

- Thompson Springs, Utah

- Tonopah, Nevada

- Wendover, Utah

Dean Jagger's scenes were shot on the Salt Lakes of Nevada. Super Soul's radio station was filmed in Goldfield, Nevada. All of Cleavon Little's scenes were completed in under three days.

Carey Loftin was the film's stunt coordinator and responsible for setting up and performing the major driving stunts. Loftin's resume at the time included work on Grand Prix (1966), Bullitt (1968), and The French Connection (1971). Barry Newman learned from Loftin and was encouraged by the stunt coordinator to do some of his own stunts. In the scene before Kowalski crashes into the bulldozer, Newman drove and performed a 180-degree turn on the road himself without the director's knowledge.

The 383 car was also used as the tow vehicle in the crash scene at the end of the movie. A quarter-mile cable was attached between the Challenger and an explosives-laden 1967 Chevrolet Camaro with the motor and transmission removed. The tow vehicle was driven by Loftin, who pulled the Camaro into the blades of the bulldozers at high speed. Loftin expected the car to go end over end, but instead it stuck into the bulldozers, which he thought looked better.

Vanishing Point was one of the cinema's prime offerings to the drive-in gods in the 1970s. I must have sat in the back seat, with my parents up front, watching this adrenaline-pumper (often as a second feature) at least ten times that decade. I vividly remember it being paired often with another searching 1971 car movie, Monte Hellman's Two Lane Blacktop, and also in re-release as part of a much-touted 1974 20th-Century Fox-powered double bill with another key drive-in car-chase classic, Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry, starring Peter Fonda and Susan George (I can also recall its appearing with Floyd Mutrix's like-minded auto-centric romance Aloha Bobby and Rose). Watching Vanishing Point recently, I realized its immutable impact on me when, ten minutes in, Kowalski's speeding car is at once stopped in freeze-frame, and then disappears from the screen. Even as a kid, I thought: "What is THIS?!" In its own way, it's as indelible a moment as Truffaut's freeze-frame climax to The 400 Blows.

Kowalski's not a bad guy. He may be a bifurcated speed addict through and through, but he has a job to do and he does it well. Stodgy badge-wearers retreat to radios, roads and sky to keep the man from doing his chore, but they amount to little more than housefly-scaled irritants. Even with his lawlessness, Kowalski's careful to ensure the safety of the civilian and non-civilian drivers he deftly runs off the dusty western byways. Differently from the heroes of a host of 1970s films, this vigorous man--an unappreciated Vietnam vet and former racetrack loser--is always thoughtful regarding those he's bested. In return, the fates hand him the victory/homecoming he always desired. This character, in his most dire moment, gets assistance from Dean Jagger (the Supporting Actor Oscar-winnner for 1949's WWII saga Twelve O'Clock High, portrays a desert-wisened snake charmer who teaches Kowalski how to truly become invisible). Amidst this movie's screeching, dust-cloud bedlam--as with the whole of the clip-clopping western genre--one of the glitziest adornments to Vanishing Point is its portraiture of the rocky, brush-covered countryside, though here the boonies are slashed not by towering buttes, but by the horizontally-angular intrusion of asphalt and white lines.

Sarafian's studied camera is captained by cinematographer John A. Alonzo, who'd later extend his grainy, rarely-showy talent to classics like Harold and Maude, Sounder, Chinatown, The Bad News Bears, Norma Rae, Scarface and George Clooney's black-and-white live-TV remake of Fail Safe (2000). Alonzo broke through to the A-list with Vanishing Point and it's no mystery why: his agile camera keeps up with that raging Dodge Charger like a battle-scarred trooper. It zooms in slightly, seemingly desirous to become one with the automobile's metallic body, spotting the white demon in long shot through the astral prism of the wavy desert heat, and then capturing it in disorienting, motion-filled close-ups as the sandy sunshine reflecting off Kowalski's windshield blinds us to this dude's actual motivations (the worst scene in the movie, which should have hit the post-production floor, mawkishly refers to Kowalski's seaside past with a long-haired blonde, who's mirrored often amongst the movie's few women; as it's inferred, she disappears in a surfing mishap). This thankfully brief moment--along with one involving an adoring, nude lady hog rider--confuses and bores the viewer, since we already know Kowalski's uber-practical aims. We don't need ladles of sentiment to satify here.

One who hasn't seen this jaunty, stunt-laden movie jewel might think that the intense, sparse lead performance by Newman is Vanishing Point's only relation to humanity. But throughout the film, we also follow Cleavon Little (more well known for his later role as the snide, self-confident lead in Mel Brooks' western spoof Blazing Saddles). He's dedicates much energy to the charismatic, out-of-place Super Soul, who uses his airwaves to comfort, forcibly deceive, and ultimately cheerlead Kowalski towards his soul destination. Little's introduction in the film is another of its treasures. Sighted, yet wearing a blind man's sunglasses--he sees nothing but he sees it all--Super Soul trails behind a German Sheperd through a small town's weedy crossroads (the pissed-off townsmen keep their mouths shut tight as he passes--he's a bizarre fixture there, but he's already given them what for, and besides, he's "handicapped," so hands off, bub). Super Soul arrives at the KOW(alski) studios--"the noisiest, bounciest, fanciest radio station in the faaaaaarrr west"--as an undisputed superstar (his first broadcasting salvo is absolutely electric). Even considering Wolfman Jack in American Graffiti, Jeff Bridges in The Fisher King, Eric Bogosian in Talk Radio, and Lynne Thigpen in The Warriors, this is surely the best performance ever by someone playing a radio DJ. Along with Wolfman Jack's performance, it's certainly the purest, since the music and not the talk seems to be his point. I do love it when Super Soul advises Kowalski that the desert will beat him; Kowalski tells him to go to hell, and switches off the radio. Later, after Super Soul and his producer (John Amos) are brutalized by the cops, Little and Newman--both equallly put-upon--seem to have an impossible conversation with each other through the ether.

Gifted with a diverse soundtrack that includes gospel, soul, hard rock, bluegrass, honky tonk and elevator music from Delaney and Bonnie Bramlett, Mountain, a way-pre "Bette Davis Eyes" Kim Carnes, Jerry Reed, and others, Vanishing Point sounds as good as it looks (it also knows how to employ silence and sound effects). The accomplished Sarafian shoots his lean story with confident aplumb. In an era where viewers were just getting over the often goony use of rear-screen projection to convince them L.A.-bound actors were completely ensconced in other places and times, Sarafian historically, bravely chose to shoot everything in Vanishing Point as if it were happening presently (now, CGI has taken the place of rear-projection, as the extra-lame remake of Gone in 60 Seconds and, conversely, Tarantino's "reality"-loving Death Proof have shown). Sarafian sternly locks the camera down upon the hoods of that Dodge Charger, and on the hoods of rival sedans, with Kowalski-like determination. The repeatedly dizzying shots of the rushing road, with white dots speeding by, and the searching, driver's-side-window close-ups of the concentrated Kowalski are waggishly exhilarating. Sarafian later delivered underrated B-product like the southern passion play Lolly Madonna XXX (with Robert Ryan, Season Hubley, and Jeff Bridges) and the compassionate Burt Reynolds western The Man Who Loved Cat Dancing. And the director would also pen a valuable production primer called The Film Director. But Sarafian would nevertheless cruelly sink into obscurity. However, with his unrelenting Vanishing Point, he definitely caught one moment where the rubber met the road.